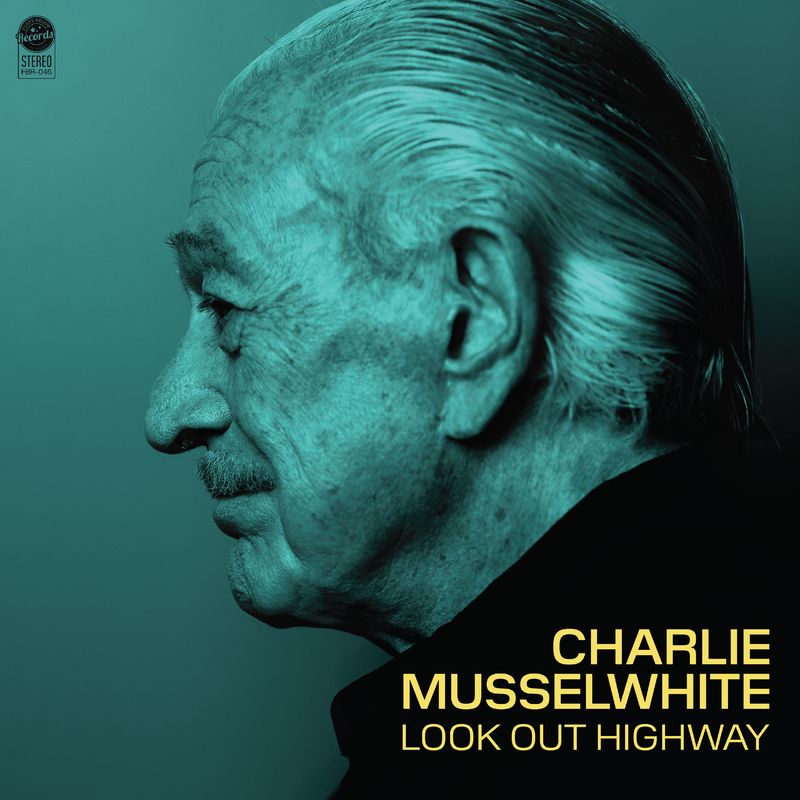

Look Out Highway may very well be the best album Charlie Musselwhite has done in a career that spans nearly six decades. For a Grammy winner with 13 nominations, 33 Blues Music Awards, and the distinction of having been the best man at John Lee Hooker’s wedding, he has consistently been one of the most unassuming interviews I ever do. I asked him the same question twice during our most recent interview: does he consider himself a legacy artist?

“I kind of think of it as I’m just a working stiff,” he said the first time I asked. “What’s the fuss about, you know? But I do appreciate that people like what I do. I just keep plugging away at it. Looks like I’ve had a career over all these years.” He chuckles. “It’s been paying off.”

I gave him another chance at an answer later in the interview, and here’s what he said: “I don’t have any romantic notions about myself as some kind of star or something. I never once did. Never had an illusion. I don’t really think of stuff like that. I think I did pretty good at what I do. People like it, and I enjoy doing it.

“I never want to be in the spotlight. I never really felt comfortable with that, but I had to be there to do what I do. When I look back it seems like it just happened without really having a plan. I still don’t have a plan. I just get up there with the best possible attitude and see where it’s able to take me.” Then he chuckles, embarrassed by the question.

He grew up in Mississippi and Tennessee, and moved to Chicago in the mid ’60s. “I’d been doing construction work and factory work. I played some music just because I loved music. If I’d never gotten a break and never recorded, I’d still be playing. It’s just something I do and decided I loved the blues and made it a career. So, when I went to Chicago, I didn’t go up there for the blues scene. I didn’t even know there was a blues scene.

“I knew nothing about Chicago except it was a big city up north that had a lot of factory jobs that pay well, and that’s why I went up there, just like thousands of other people leaving the south for that big factory job up north. When I got up there and discovered the blues scene, I just started hanging out at all the clubs.

“It was all there: all the blues heroes, all the clubs. And it was great being in a club and hearing Muddy Waters live, Howlin’ Wolf live, Little Walter live, Sonny Boy… I met ’em and talked to ’em, but I wasn’t going around asking to sit in or anything. I didn’t think that was anything I could do. I didn’t know anything about the music business. I was just working in the factory, you know.

“This waitress who worked at Pepper’s lounge told Muddy, ‘You oughta hear Charlie play harmonica.’ Up until that point, Muddy thought I was just a fan because I would request some old tunes. I remember him saying, ‘How do you know that tune?’ I answered, ‘I got the record.’

“So, it tickled him that I knew those old obscure tunes, and then when he found out I played that just changed everything. He insisted I sit in. A lot of musicians at Pepper’s Lounge heard me playing with Muddy and started offering me gigs. Boy, did that give me focus.”

His first recording was Stand Back in 1967. American music historian, writer, record producer, musician, and poet Sam Charter produced that first album. “When we got into the studio, Sam Charter said, ‘You only have three hours because if you go over three hours, Vanguard would have to pay double scale.’ They weren’t going to do that. So, we just knocked ’em out one after another.”

Blues historian and author Pete Welding wrote the liner notes. Welding’s producing credits include Robert Nighthawk, Bo Diddley, and Quicksilver Messenger Service: “As this first recording suggests, Charley (Note the misspelling) is right now one of the handful of young blues interpreters who have succeeded in penetrating beyond the surface of the music to the development of a thoroughly satisfying, recognizable personal approach to the modern blues. In the coming years, his single-minded dedication to the music, his ever-deepening technical skills and his thirst for new ways of expression are sure to yield an ever-richer musical harvest.”

What an understatement!

Charlie picks up the story. “When it came out, I don’t think I had any idea what it would do, but it sure put me on the road with a career. I’ve been playing professionally ever since. I’m thankful for standing pat for a whole career. There have been a lot of ups and downs, but I just stayed in there.”

Harvey Mandell played guitar on that first recording. Barry Goldberg was on piano and organ. The bass player was Bob Anderson. Fred Below was the drummer on the three-hour session. “Fred was a good friend, too. We did a lot of touring together all across the United States. He just played a sweet shuffle, boy, and I just loved what he did. He was the kind of drummer when he was playing behind you, you just felt like you were sailing across the top of it all. He had a way of propelling you, and it’s hard to explain, but he had better ideas. If I was playing a solo with Fred pushing me, I just played better. I think everybody did.”

Charlie would go on to collaborate with Ben Harper, Cyndi Lauper, Eddie Vedder, Tom Waits, Bonnie Raitt, The Blind Boys of Alabama, Gov’t Mule, INXS, Mickey Hart and Japan’s Kodo Drummers, George Thorogood, Eliades Ochoa, Cat Stevens, Elvin Bishop and, close friend John Lee Hooker. In 2010 Charlie entered The Blues Hall of Fame. And in 2023 he appeared in Martin Scorsese’s film Killers of the Flower Moon.

Charlie has been a prolific songwriter throughout his career. He keeps a folder in which he writes ideas for songs. “It’s a folder full of little pieces of paper. In fact, it’s probably a half dozen folders (that) I have in the motel, in the van on the way to the gig, or backstage. I hear something that makes me think of something. It comes from all kinds of places. And I just write ’em down. It goes in the folder, and later when I’m writing songs, I’ll get all those pieces of paper and look at ’em. Some of ’em seem to go together, and they (make) a song.

“Some songs just seem to come together in minutes. Others I just keep working ’em for years, and finally I just get rid of ’em, but they first come in different songs. Some of ’em just seem to show up ready to go. I don’t know where they come from. They just surface in my head.”

Much of the just released album Look Out Highway was recorded with Charlie’s touring band at Kid Andersen’s Greaseland Studio. “It was just time and we just finished a gig in New York City at the Iridium. The pandemic was setting in, and suddenly we had time on our hands. So, it made sense to record. Actually, a lot of it was done in Clarksdale at the Clarksdale Sound Stage. All the vocals and harmonica parts are from Clarksdale. All the basic tracks were done at Dreamland Recording in San Jose, and there was some problem with the recording. I had to redo vocals and harmonica at the Car Sale Sound Stage which, by the way, is a couple blocks from my house. So, it would go easy.”

Ten of the 11 songs are originals that present the singer as a rather scurrilous character who brags that “Ramblin’ Is My Game,” the complete opposite of Charlie’s real-life demeanor as a devoted husband. His wife is his manager.

Loaded with single entendres, he asks one woman, “Baby, Won’t You Please Help Me.” He’s enamored by another who has “Sad Eyes.” Charlie again flipped through his book of words and stories until he “found the scent,” casually painting the picture of two people filling a void for each other, pretending to love, knowing it’s not going to last.

“Storm Warning” is the oldest song on the record. “I remember writing it. It was 30 years ago, but it was about half an hour or something. So, I’ll run it down. I’ll have a song, but as I do the song, a crack comes through, and I keep getting better ideas. I keep changing a word here and a word there or a sentence. The more I think about it, it will evolve, and it will just come into my head a better way it should go. I thought it would be a great one to cut with my band. I’d heard songs comparing women to highways with ‘curves’ and ‘soft shoulders,’ etc., but I got to thinking that weather comparisons could also be good. I’ve witnessed some stormy relationships with plenty of rain!”

“Ghosts of Memphis” probably comes closest in representing the reality of being an 81-year-old blues musician. “I grew up in Memphis, and spent a lot of time getting to know the last of the old blues singers. Going to Memphis now, most everybody I knew is dead.”

The album is his first for Forty Below Records whose recent releases include works by Joe Louis Walker and Danielle Nicole. Label founder and producer Eric Corne has been quoted as saying, “Working with an artist of Charlie’s caliber is an honor and privilege. He’s one of the most iconic blues musicians working today, and we look forward to taking his legacy to the next level.”

Charlie Musselwhite and I are both Aquarians. He was born January 31, 1944. I was born two days later. Neither one of us is done yet.